When I was a schoolgirl Mastermind was one of those programmes I always thought took precious airtime that could be used by something else, something more interesting. As I became older, I began to realise that the reason I felt this way was not because I was a big fat ignoramus, but because I had always associated the programme with white, middle-class ‘intellectual’ men, specialising in subjects that I had been conditioned to believe were not accessible to me (quantum physics, aviation engineering…etc…) – anything seen as ‘respectably intellectual’ really. Where I come from women are not meant to be thinkers, it’s actively frowned upon, and I’m sure that this is the case for a lot of women out there.

Although I am yet to be awarded a PhD in molecular biology (it’s not looking likely, I must confess), and still know as little about quantum physics as I always have done, I realise now that these are, and always have been, subjects accessible to women, subjects we have made huge strides in, as is the possibility of reigning triumphant when sat in the big black chair. Learning has, wrongly, traditionally been seen as something only seriously pursued by men. Maybe this is because we were denied education for such a long time, unable to fulfil out academic potential, but it’s unfortunate that archaic ideas still permeate the national consciousness to a certain extent. This is despite the fact that young girls are consistently shown to be outperforming their male counterparts in school, and women are just as capable as men in the workplace (the latter being something that should not have to be stated).

But this is something the producers of Mastermind are hoping to address, according to an article in The Guardian yesterday. The presenter, John Humphreys, allegedly recently “bewailed the shortage of women on the show,” sparking a campaign to rectify the gender imbalance of contestants applying. According to the article, between 1,500 and 2,000 people audition for the programme every year, but only a quarter are female. In the shows 35-year history, 21 men in comparison to just 8 women have taken the title, the last woman victor being the novelist Anne Ashurst in 1997.

Mastermind, in an attempt to attract the ladies, has started to advertise in women’s magazines and has approached women’s organisations. Although this is to be commended, there is something distinctly patronising about this plight, as highlighted by a spokesperson for the BBC:

“Women will still have to be good enough to get on the programme. Mastermind is looking at encouraging more women to apply because they are not getting as many as men.”

So, if you were hoping that positive discrimination was going to work in your favour, or Mastermind was going to lower its standards to allow you to drift through the audition process just because of your genitalia, then you are very much mistaken. Surely this comment in itself draws on the perceived, and unsubstantiated, intellectual disparity between men and women? To state that women “still have to be good enough” to appear on a TV show that does favour men instantly sets up a comparison with the latter, and implies that men are, after all, setting the bench mark, and us little ladies are going to have to try our hardest to keep up with them despite our bouffant hair and giggly personas. This did not need to be said by the BBC, and ironically all such redundant statements do is to imply that the antithesis is the case – that women may be given certain concessions, which undermines the whole premise of the campaign, and will also place a question mark over the calibre of female applicants (which is the most unfair result).

Maybe this was a case of semantics, that what the spokesperson was merely trying to impart was that all the contestants who apply have to display a certain academic standard, although what was said has a very different meaning, and maybe to endores that idea is to give the BBC benefit of the doubt that it does not deserve. In some respects the implication is that we should be grateful to Mastermind for providing us with the opportunity, something we, unlike men, have been unable to create for ourselves, although ironically in the process it’s consolidating the stereotypes that originally made it seem inaccessible to us in the first place.

The article does not state what women’s magazines have been used to display advertisements, nor the nature of the advertisements, although hopefully a pink chair doesn’t feature at all. Although, that said, if this does have the affect of encouraging more women to apply, then it is only a good thing, since we would have an opportunity to help eradicate redundant archetypes through action.

It may also possible, however, that women generally just don’t want to feature on the show; that we don’t need to spend half-an hour in a wheelie chair to validate our intelligence, and so the idea that we are supposed to (and should be) aspiring to this is something that needs to be addressed. Everyday we are told that we should and do want something – would it be too much for someone to ask us what it is we do want, instead of wildly speculating to such an extent that when we do make claims we are never taken seriously? The Guardian article does not contain any comments from women stating their opinions about the show, and I was unable to source any online, which bolsters this idea.

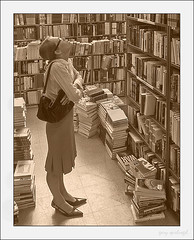

Photo by Your Guide, shared under a Creative Commons License.